Advertising vs. Obesity

Between 5-25 percent of children and teenagers in the

Between 5-25 percent of children and teenagers in the

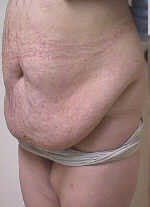

There are three main categories that have cause obesity among young adults or kids, namely the family; low-energy expenditure; and heredity. The risk of becoming obese is greatest among children who have two obese parents (Dietz, 1983). This may be due to powerful genetic factors or the significance of this is small when compared to other factors potentially linked to childhood obesity such as exercise, trends in family eating habits inside and outside the home, parents’ demographics, school policy understanding of nutrition, food labeling and other forms of food promotion. The evidence from Ofcom’s research shows that 70% of children’s viewing takes place outside of children airtime, traditionally defined as the after-school slot on weekdays, Saturday mornings and throughout the day on dedicated children’s channels and cable and satellite.

Nevertheless, since not all children who eat non-nutritious food, watch several hours of television daily, and are relatively inactive develop obesity, the search continues for alternative causes. Heredity has recently been shown to influence fatness, regional fat distribution, and response to overfeeding (Bouchard et al., 1990). In addition, infant born to overweight mothers have been found to be less active and to gain more weight by age three months when compared with infants of normal weight mothers, suggesting a possible inborn drive to conserve energy.

Somehow many commentators have called for restrictions on food advertising justified by an assumption that such restrictions will help to fight childhood obesity. To date, efforts to restrict commercial speech have been focused on children, rather than adults, although in practice regulatory efforts will obvious spillovers. One justification for targeting efforts at childhood obesity is that being overweight or obese as a child substantially increases the likelihood that one will be obese as an adult. Nonetheless, there has been little theoretical or empirical analysis of the central questions related to the advertising causes obesity thesis.

Stated simply, the theory is premised on the assumption that advertisement of food products alters consumer’s preferences for foods so that they consume more of the advertised food than they would have absent the advertising. For example, ads for fast food cause increased overall consumption of fast food in addition t causing some people to switch from one fast food brand to another. In principle, this effect of advertising applies to both adults and children, with the primary distinction being that adults are better able to perceive and defend themselves against advertising. Reason being, adults are more educated and aware of what categories of foods are advisable to be consumed a lot and which should not be. Yet, adults are not easy to get influenced by the ads as they will reconsider before purchasing the products as compared to kids or young people who do not know much about the food content, or somewhat do not bother the consequence of being over consumed. As applied to the issue of childhood obesity, it is observed that there is a substantial amount of advertising for relatively unhealthy foods, such as sugared cereal, candy, salty snacks, and the like.

Marketers are competing among others in order to gain the most market share of all, by enhancing their products, attach with complementary bundling. Whenever kids watching the TV commercial, together with interesting freebies advertise on the screen, they tend to nag in front of their parents to buy them the foods. Sometimes we could not just hundred percent blame on the demonize advertising of luring the children to select their particular brand. Why? Will the kids actually drive themselves to a supermarket to get the stuff? Will they have that much money to spend on it? That could be ridiculous obviously. Parents are pampering their children by trying to get what they want, as long as the children are happy with it. Nevertheless, measures of the parents’ habits indicated they had a significant impact on their children’s calorie intake and the nutritional quality of their diet. Parents’ eating behaviour was substantially more important than advertising in influencing children’s dietary habit.

As a conclusion, food advertising is not a primary causal factor in children’s increased obesity rate. Furthermore, there may be negative consequences to banning or restricting truthful food advertising. As the public becomes more educated on the importance of weight control to health, there may be increased pressure in marketers to compete on calorie content; food ad restrictions could inhibit such competition. Some changes in food labeling rules could  play an important role in bringing information to consumers and adding to firms’ incentives to focus on the calorie profiles of their foods.

play an important role in bringing information to consumers and adding to firms’ incentives to focus on the calorie profiles of their foods.

References:

Anup Shah, 2005, ‘Health Versus Unhealthy Food Marketing; Who Usually Wins?’, Global Issues, viewed 17 March 2006, http://www.globalissues.org/TradeRelated/Consumption/Obesity.asp

Lee Drutman, 2001, ‘America the Fat’, Philadelphia Inquirer, Alter Net, viewed 17 March 2006, http://www.alternet.org/story/12110/

‘Call for TV food ads ban’, 2003, BBC News, viewed 17 March 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/3238255.stm

‘Minister cold on junk food ad ban’, 2004, BBC News, viewed 17 March 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/3528537.stm

Kaye Mehta, 2002, ‘Childhood obesity and television food advertising to children’, Coalition on Food Advertising to Children, NSW Childhood Obesity Summit, viewed 17 March 2006, http://72.14.203.104/search?q=cache:2JO_wl4rs6IJ:www.chdf.org.au/i-cms_file%3Fpage%3D664/NSWSummitStatemnt0209.PDF+contribution+of+advertising+to+obesity&hl=en&gl=my&ct=clnk&cd=37

Obesity, Debate – Issue Briefs, 2006, Politics.co.uk, viewed 17 March 2006, http://www.politics.co.uk/issues/obesity-$3356637.htm

Brian Young, 2004, ‘Does advertising to children make them fat? A skeptical gaze at irreconcilable differences’, Children as Consumers: Public Policies, Moral Dilemmas, Academic Perspectives, viewed 17 March 2006, www.consume.bbk.ac.uk/conference/childconsumer/Brian%20Young%20paper.doc –

Judith Blake, 2002, ‘Expert blames obesity on food-industry marketing’, The Seattle Times, viewed 17 March 2006, www.foodpolitics.com/pdf/expblameobe.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment